Commentators in the United States and Israel have hailed the agreement on the maritime border between Israel and Lebanon, which the Biden administration recently brokered, as a great success. They liken it to the Abraham Accords and claim that it is a major step toward normalizing relations between the Jewish State and a historic Arab foe. But a close examination of the agreement simply does not support this view.

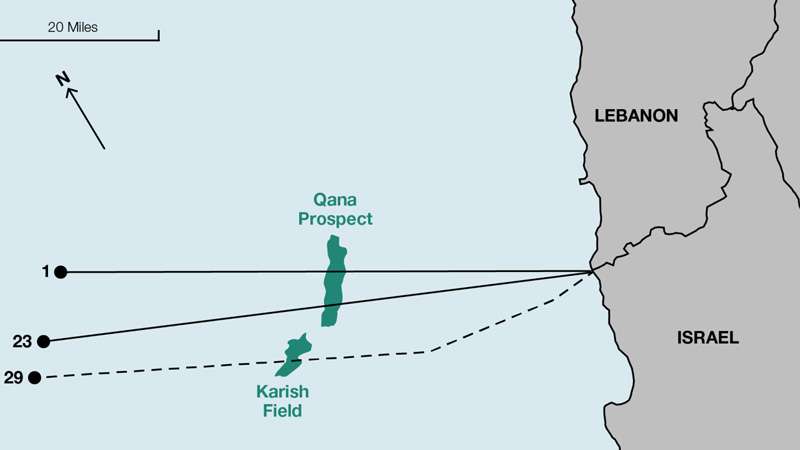

Amos Hochstein, the US State Department senior advisor for energy security, led the mediation effort to resolve this dispute. He built on the initiatives of Presidents Barack Obama and Donald Trump to reconcile the conflicting claims of Israel, which claimed Line 1 (see map) as the northern border of its exclusive economic zone (EEZ), and Lebanon, which claimed Line 23 as its southern border.

In the final months of the Trump administration, Lebanese negotiators revised their claim, moving it further south to Line 29. Beirut, however, never registered this new claim with the United Nations. In other words, Line 23 always remained the official Lebanese position. When Hochstein arrived in Beirut last February, the Lebanese government abruptly dropped its insistence on Line 29 and presented its retreat as a sign of its flexibility, a compromise proposal that it could withdraw if the negotiations failed to produce satisfactory results.

The belated and halfhearted adoption of Line 29 appeared capricious. But the Lebanese were manufacturing a pretext for claiming that Israelis had no right to pump gas from the Karish gas field, Israel’s northernmost field. Karish lies well south of Line 23, but Line 29 dissects it. If the Lebanon-Israel border falls along Line 23 or along another point further north, then the Karish field lies entirely within the Israeli EEZ. By making Line 29 part of the discussion, however disingenuously, Beirut postured itself to claim that Karish lies, in part, in Lebanese waters and that Israel’s exploitation of it constitutes the theft of Lebanon’s resources.

The full value of this tactic became apparent last June when the floating rig for exploiting Karish arrived in Israeli waters from Singapore, where it was manufactured. Lebanese President Michel Aoun and Hassan Nasrallah, the secretary-general of Hezbollah, used the arrival of the rig as the starting bell for a tag-team effort to pull the Americans into the dispute on the side of Lebanon.

Aoun warned Israel that any activity in the area “constitutes a provocation and a hostile act.” He then invited to Beirut Amos Hochstein, who arrived in mid-June. Shortly thereafter, Hassan Nasrallah launched drones, almost certainly acquired from Iran, toward the rig. In addition to intimidating the Israelis, the goal was to instill a sense of urgency in Hochstein and his colleagues in Washington. On July 13, Hassan Nasrallah delivered a speech in which he gave Hochstein and the negotiators two months to produce results. “If we do not get what we rightfully want from the negotiation, there will be a higher cost. Our drones will fly beyond Karish,” he said.

The tag team effort paid off. President Joe Biden, for his part, personally adopted Nasrallah’s timetable. When the president spoke with Lapid in August, he “emphasized the importance of concluding the maritime boundary negotiations between Israel and Lebanon in the coming weeks,” according to the White House. Under military pressure from Hezbollah and diplomatic pressure from Washington, Israel did what it had refused to do for over a decade: dropped its claim to Line 1 or to any compromise position and accepted instead Line 23, the Lebanese position.

In summary, the United States encouraged Israel to concede to all of Hezbollah’s demands. In return, Lapid claimed that Israel had avoided conflict, acknowledging that under pressure he compromised for a period of quiet that will last until Hezbollah, who is under no obligation to anyone, decides to end it.

Below are seven myths about the Israel-Lebanon maritime border agreement, and clarifications about what the deal means.

map israel lebanon border gas dispute

Source: Dario Sabaghi, “Explained: Renewed Israel-Lebanon Maritime Border Dispute,” Middle East Eye, June 11, 2022, https://www. middleeasteye.net/news/explained-israel-lebanon-maritime-border-dispute-renewed.

Notes: Line 1 was Israel’s claimed maritime border. Line 23 was Lebanon’s claimed maritime border, and will likely become the official border. Line 29 was Lebanon’s revised claim that Beirut did not register with the United Nations.

Myth 1: “The agreement will make Lebanon less dependent on Iran.”

Reality: Lebanon is famously corrupt and controlled by Hezbollah, which in turn is controlled by Iran.

The usual cronies will divide the money among themselves, and Hezbollah will get its share. Enriching the fictitiously independent state of Lebanon without enriching Hezbollah and Iran is impossible. So the agreement will not reduce Hezbollah’s grip on the government in any way.

Myth 2: “Israel needs this agreement to proceed with the exploitation of the Karish field.”

Reality: Energean, the company that Israel contracted to develop the Karish gas field, began its work when it looked as if there would never be a deal with Lebanon, and it continued to work when Hezbollah threatened war.

From a commercial point of view, the agreement was irrelevant. The world is replete with examples of companies that exploit gas fields within undelimited or even highly disputed EEZs. When deciding where to work, the companies rely on the security and financial assurances of their host countries, not on international agreements. Lawyers from the United Nations never saved workers on a gas rig caught in the crossfire of hostile militaries.

But even from a strictly legal point of view, Israeli ownership of Karish was never the issue. The Lebanese always staked their claim, officially, on Line 23. The Karish gas field, lying well south of that line, was therefore clearly in Israel’s EEZ.

As for Nasrallah, he did not threaten to attack because he considered the exploitation of Karish to be an especially provocative or hostile act. Nasrallah has made clear that he sees the existence of Israel as a gross and ongoing injustice, an affront to all Muslims, and a threat to Lebanon. “Where is our sea?” he asked in a speech on October 11, after the maritime border agreement was completed. “To us, our sea extends to Gaza,” he answered. From Nasrallah’s point of view, the oil refinery in Haifa and the power plant in Hadera are as much an affront as the Karish rig.

Myth 3: “The deal is a major defeat for Hezbollah and Iran.”

Reality: Nasrallah and Iranian Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei have every right to celebrate this agreement as a major victory, a capitulation by both the US and Israel.

A “historic achievement,” is how Hezbollah’s Deputy Secretary-General Naim Qassem described the demarcation agreement on October 15. “The Resistance [Hezbollah] had a great impact on securing the maritime oil and gas rights for Lebanon,” he continued. “This matter would not have happened without the solidarity between the state and the Resistance.”

Who can argue with that assessment? Hezbollah received everything that it demanded within the timeline that it set. Israel made every conceivable concession; Lebanon made none. Supercharged American mediation rewarded Hezbollah for threatening war.

The proper American answer to Hezbollah’s drone launches would have been a strong statement affirming Israeli ownership over the Karish gas field and emphasizing Israel’s right to self-defense. To the Lebanese politicians, American diplomats should have stressed that the United States will join them as a mediator only after they agree to sit down directly with their Israeli counterparts.

In the meantime, traditional military deterrence, not appeasement, is the only way to contain Hezbollah—and not just Hezbollah. Military deterrence is also the answer to the threat posed by Iran and all its proxies. Biden’s call to Lapid coincided with the Biden administration’s efforts to finalize the negotiations with Iran on the nuclear deal. So Biden may have encouraged Israeli concessions to sweeten the pot for Iran.

Myth 4: “This agreement will help alleviate the European energy crisis.”

Reality: The agreement will have no impact on Europe whatsoever.

Only future historians will know with certainty whether the White House prioritized the Israel-Lebanon deal to reconcile with Iran. But strikingly, the deal lacks any other discernable strategic imperative. Hochstein could have focused on myriad other issues that are more critical—including, for example, working to solve disputes between NATO allies Greece and Turkey over their EEZs, or bringing gas to Europe from Turkmenistan, which has some of the world’s largest reserves. To justify the quixotic choice of priorities, commentators have claimed that this deal will somehow alleviate the European energy crisis. It will not. There is no guarantee that Lebanese gas will ever come on the international market. If it does, it will not appear for another five to ten years—by which time the European energy crisis will be history. As for the Karish field, Israel has from the outset designated its gas for local consumption only, not export. The field is also very small and will have no appreciable impact on gas prices. In any case, Karish, as noted above, would have come online without the deal.

Myth 5: “The deal advances Arab-Israeli peace.”

Reality: The deal advances nothing.

In announcing the deal, President Aoun stressed that “no normalization with Israel took place,” and he refrained from thanking the Israelis for the concessions they made. He did, however, thank Hezbollah. When making this agreement, no Lebanese official met an Israeli official or spoke to one on the phone. There will be no joint signing ceremony, and certainly no handshake on the White House lawn.

While explicitly refusing to make any agreement with Israel, Lebanon pointedly made an agreement with the United States about the location of its southern maritime border. Line 23, the newly agreed upon border, dissects the Qana prospect (see map), an unexplored field from which Lebanon expects to pump gas. Here again, Lebanon refused to make a deal with Israel about joint exploitation of the field. Instead, Israel will work out a deal with TotalEnergies SE, the French company that has the rights to exploit the Qana prospect. The (yet undetermined) compensation that Israel will receive is not for the area it forfeited but for the small section of the Qana prospect south of Line 23, which is firmly in Israel’s EEZ. Lebanon will have no role in the negotiations between Israel and the company, which will serve as a buffer between the states. Although the Qana prospect straddles the border, it will not promote cooperation.

Observers have also claimed that the deal represents a tacit recognition, for the first time, of Israel by Hezbollah. This is categorically false. Hezbollah has previously negotiated, for example, prisoner exchanges through intermediaries with Israel. The organization certainly admits that a “Zionist entity” resides to the south of Lebanon. How could it not? The point of recognition is to acknowledge legitimacy, something Nasrallah vehemently refuses to confer upon Israel. This maritime border agreement tacitly recognizes Israel only in the same way that every missile Hezbollah launches at Israel tacitly recognizes it.

Myth 6: “This deal promotes peace by making Israel and Lebanon-Hezbollah economic partners.”

Reality: In no universe is making Hezbollah a partner of Israel a good thing.

Just a few short years ago, influential voices in both the United States and Europe scoffed at the mere suggestion that Germany’s economic partnership with Russia on natural gas would expose Berlin to extortion by Moscow. On the contrary, they said, Germany would rope Russian President Vladimir Putin into a mutual dependency, one that would turn him into a “stakeholder” in regional stability. Rarely in international politics have events discredited a strategic thesis so quickly and so totally. But even as the Russia-Ukraine War rages, commentators are applying the same flawed calculus to relations between Israel and Hezbollah.

One version of the economic-partnership argument claims that the two gas rigs, one Israeli and one Lebanese, operating close to one another will hold each other hostage. But the next war that will break out between Hezbollah and Israel will likely start elsewhere. When it does erupt, the two rigs’ “coexistence” will hardly influence events. Nor, for that matter, will their “coexistence” spare Israel’s gas platform. If Hezbollah sees utility in destroying the Israeli rig, it will do so with glee. The Israelis, however, will be more restrained. They will hesitate before attacking the Lebanese rig, if one should ever exist, because TotalEnergies SE, which will be compensating Israel for the Qana prospect, will own it.

Myth 7: “This deal will dramatically reduce tensions between Israel and Lebanon by removing a major irritant in relations.”

Reality: The removal of this or that grievance of Hezbollah today will do nothing to prevent the fabrication of new grievances tomorrow.

Hezbollah is a wing of the Qods Force of the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps. From the point of view of Tehran, the Lebanese terrorist group constrains Israel and deters it from attacking Iran. If war suits either Nasrallah or his Iranian overlords, Hezbollah will manufacture a pretext for starting one. Lebanon’s politicians will help Nasrallah concoct new pretexts for conflict, just as they concocted the claim to Line 29.

The best that can be said of the maritime border agreement is that it may have bought a limited period of quiet while Israel begins to exploit the Karish field. But America bought this quiet with protection money—money, moreover, that it extracted from Israel’s hide. By encouraging Israel to pay for protection, the US set Hezbollah up to present itself as the savior of Lebanon rather than the architect of its misery. In addition, the deal weakened Israeli deterrence. There will surely be another round of violence with Hezbollah. When that inevitable day comes, Israel will have no choice but to buy quiet as it has always done—either with military force or the credible threat of it. Seen in that context, the deal undermined Israel’s deterrence because it taught Hezbollah and Iran that a threat of war will trigger American mediation.

While the caretaker Israeli government is willing to help the United States sell this policy to its own public, many, probably most, Israelis know appeasement when they see it. It is no surprise, therefore, that the Lapid government is not putting the agreement to a vote in the Knesset.

In sum, the maritime border agreement belongs not in the Abraham Accords frame, but in the Iran-appeasement frame. When the Biden administration came to power, it did not hide its disdain for the Abraham Accords, even refusing to call them by name. The popularity of the accords, however, has forced the administration to pretend to regard them as a positive development. Although the White House and its supporters now pay lip service to the accords, they cannot bring themselves to support a policy that seeks to counter Iran aggressively—the key policy that made the accords possible.

Instead, they have chosen to dress up their preferred policy of Iran appeasement so that it looks like quasi-normalization with Israel, a kind of Abraham Accords lite. In doing so, the Biden administration has taught both Hezbollah and Iran that Washington stands ready to deliver concessions from America’s allies, including Israel, to “deescalate” conflicts in the Middle East.